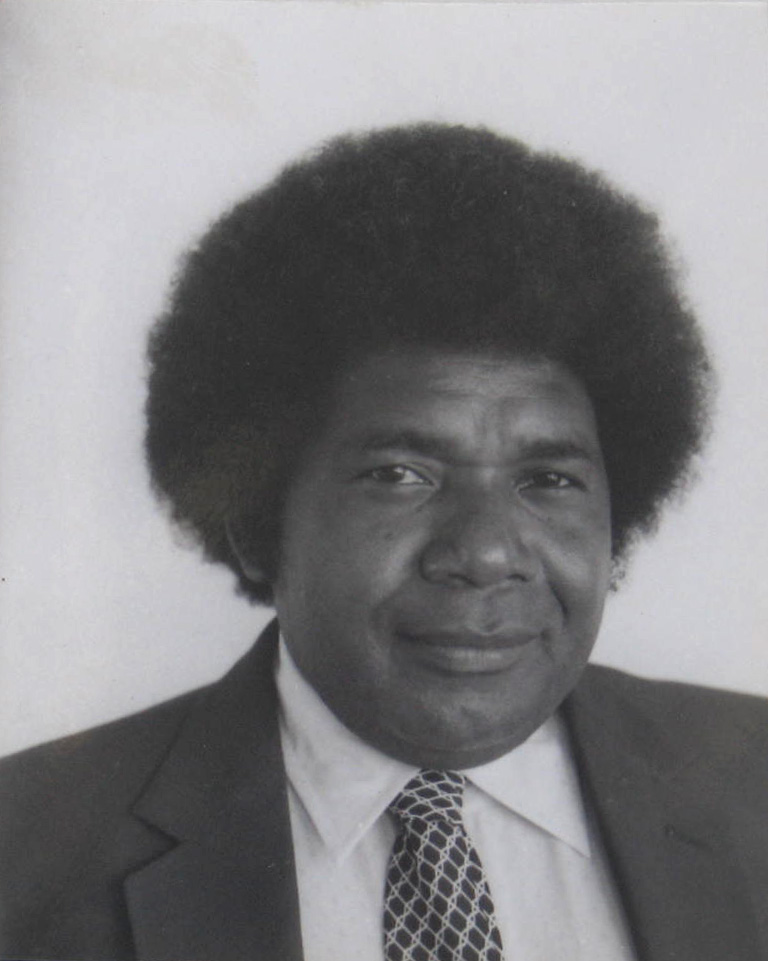

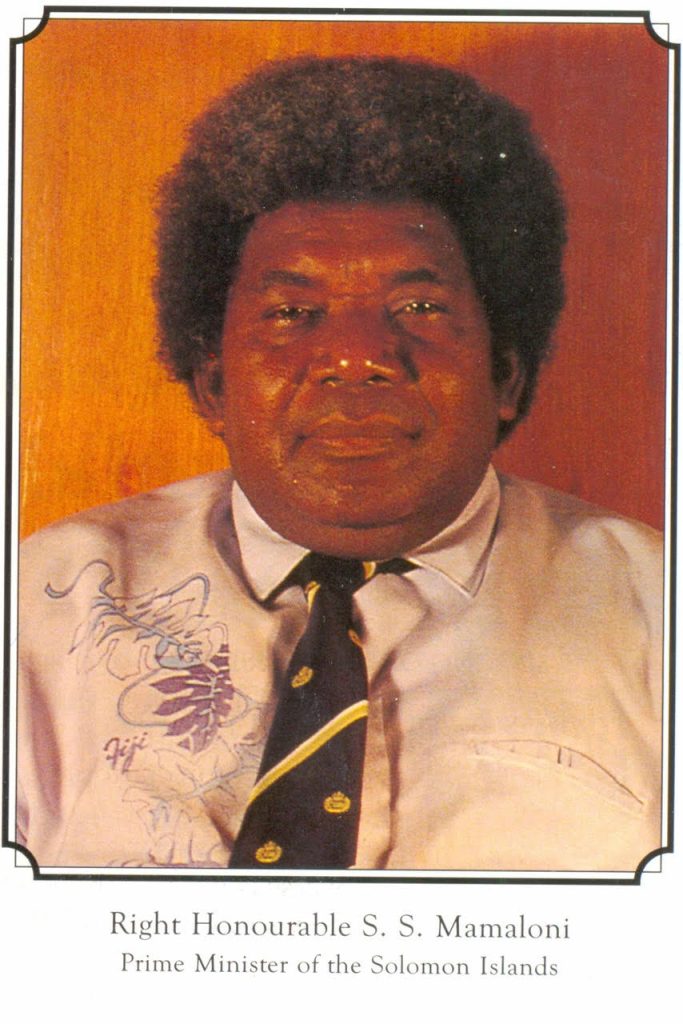

THIS month marks the 25th anniversary of the death of Solomon Mamaloni, one of the foremost founding fathers of the nation. ‘Solo’, as he was popularly known, was only 56 years old when he died on 11 January 2000 at Central Hospital in Honiara.

It is just over half a century since he became the first chief minister of Solomon Islands in 1974 and led the country to self-government status in 1976 and then as prime minister three times from 1981 to 1984, 1989 to 1993, and 1994 to 1997.

Solomon Sunaone Mamaloni was born on 21 January 1943 at Rumahui, in Arosi on the west coast of Makira, during the final weeks of the Battle of Guadalcanal, which was a major turning point in the war against Japan, Mamaloni’s early life was hardly traditional because he was brought up in the South Sea Evangelical Mission (SSEM) church, which forbade and denigrated traditional cultural beliefs and practices.

His parents, Bethseda Irageni and Joash Sunaone, separated and remarried when he was around three years old and he was raised by his beloved grandmother Emure Mwaeo, who had been adopted from Small Malaita.

Like many children at the time, Mamaloni suffered badly from tropical yaws (Treponema pertenue) and was cared for by his grandmother and young aunt Ha’arebi. He learned traditional stories and ways of life from his grandmother and by listening to elders when Rumahui was a Maasina Rule taon or stronghold from 1947 to 1951.

His father became a plantation manager and close family friend for Frederick Campbell, the first District Officer (DO) for Eastern District from 1918 to 1919, who became the largest copra plantation owner. Sunaone was elected to the Makira Council in 1955 and its President in 1958, and thus appointed to the Protectorate’s Advisory Council in 1958 and Legislative Council from 1960 to 1963.

It was his father’s name and reputation that provided the platform to Mamaloni being elected to the new Governing Council in May 1970.

From 1952 to 1959, Mamaloni was educated at Melanesian Mission (Anglican) schools, first at Waimapuru, 25 km to the west of Kirakira, and then at St Barnabas’ Junior Primary School (Alangaula) and All Hallow’s Senior Primary School (Pawa), on Ugi Island off the north coast of Makira. Mission schools were strict, run with colonial and missionary certainty.

A talented runner and soccer player, Mamaloni enjoyed sporting success, as well as friendships and popularity. A bright young man, he then went to the government King George VI Secondary School (Aligegeo) on Malaita from 1960 to 1963, where he was educated along with many future leaders, including Peter Kenilorea.

Mamaloni finished his secondary education at Te Aute Maori College in New Zealand from 1964 to 1965, where he learned a great deal about Maori history, pride, strength and leadership in the face of colonial duplicity and violence.

Although he failed his Cambridge Certificate and university entrance exams, he still enjoyed the prestige and advantages of a small elite being educated to take over at independence.

Mamaloni joined the colonial service as an administrator in 1966, but at a lower level than those who had passed their exams andtherefore eligible to become district officers and district commissioners, like his future rivals Peter Kenilorea and Francis Aqorau.

His public service career was short, and he did not endear himself to his colonial bosses or more conscientious colleagues. He worked from 1966 to 1968 in district administration under a variety of colonial administrators, some of whom were strict yet sympathetic, while others were arrogant and detestably racist.

After several poor annual probation reports, he had the good fortune in 1968 of being appointed Assistant Clerk to the Legislative Council, where he learned parliamentary procedures and oratory, which gave him considerable advantage when he entered politics.

At the age of 27, less than five years after leaving school, when Mamaloni was elected to the Governing Council he announced himself as a radical voice and a firebrand who challenged colonialism and British rule. He became the country’s first chief minister in August 1974 and led the country to self-governing status in 1976.

However, after less than two years, he resigned over the Letcher Mint Affair relating to commemorative coins celebrating self-government. Although he was quickly reappointed, he had lost political support when it came to the last election before Independence. In 1976, he was replaced as chief minister by the newly elected Peter Kenilorea, who led the country to independence in 1978 and the honour of becoming the country’s first prime minister.

Mamaloni resigned from politics in 1977 to look after his PATOSHA business interests. However, he soon returned to politics, winning back the seat of West Makira in the 1980 elections, which he retained until his death.

His secure electoral base allowed him to concentrate on national politics but he achieved very little in terms of development for his own electorate or island, although he was generous with personal donations and small project funding.

In 1981, he engineered the fall of the Kenilorea government and became the country’s second prime minister. Mamaloni introduced important measures on devolution and localisation.

He established diplomatic relations with Taiwan and allowed entry to Asian companies to log customary land. After the 1984 election, he spent most of the remainder of the 1980s as Opposition Leader, where his political and oratory skills kept the Kenilorea and Alebua governments on the defensive.

He swept back to power in March 1989, with the strongest parliamentary position of any leader before or since. By November 1990, his erratic leadership and personal life had cost him the support and respect of other party leaders.

He orchestrated a lightening political coup to retain power, dismissing five cabinet ministers and replacing them with five members of the opposition, including Sir Peter Kenilorea.

This consolidated his reputation as the political grandmaster and proved to be the high-water mark of his political career.

Under Mamaloni’s administrations, the public service was politicised, colonial bureaucratic systems were undermined, and public servants were corrupted or demoralised.

Logging interests increasingly infiltrated politics and kept government expenditure afloat, while creating a new class that was rich from revenues from corrupt deals and unsustainable resource extraction.

Meanwhile, the independence struggle and civil war on neighbouring Bougainville from 1988 to 1997 ratcheted up tensions with neighbouring Papua New Guinea (PNG) and militarised the Royal Solomon Islands Police Force with weaponry that later had a direct bearing on the ethnic tensions from 1998 to 2003.

By 1997, ill health was affecting Mamaloni’s performance, and he became increasingly reclusive, operating in the political shadows. He was weary of politics and, although he returned as opposition leader after two failed no-confidence motions against the government of Bart Ulufa’alu in late 1998, he was yesterday’s man.

He brought the newly elected Manasseh Sogavare under his wing and greatly influenced him as a political strategist, which later helped Sogavare exceed him as the country’s longest serving prime minister.

Mamaloni refused to travel to Australia for medical treatment and, with no resources for dialysis in the country, he died from complications of end-stage kidney disease a few days into the new millennium.

Always larger than life, popular stories continued to circulate after his death—notions of an underground army that could restore Makira’s autonomy and strength during the Tension.

Opinions about Solomon Mamaloni remain divided and probably continue so among those who remember him. Widely regarded as a man of the people, he epitomised the genial easy-going style of Solomon Islanders.

A great teller of jokes, he would stori and chew betel nut with anybody, young and old. Because of this he was popular with ordinary people, as was shown by the crowds who flocked to pay their respects after he died.

As a leader, he was a staunch nationalist who deeply mistrusted and often offended foreign governments and donors. Mamaloni rebelled against past and present colonialism, whether it was from Britain, the US, Australia or France. His foreign policy included the recognition of the Republic of China (Taiwan), which guaranteed generous support for Solomon Islands in its diplomatic stance as ‘friend to all people and enemy to none’.

In domestic politics, he was much criticised at the time. In a deeply Christian country, even his supporters disapproved of his multiple marriages and indiscretions.

He was held responsible for promoting the unsustainable exploitation of Solomon Islands’ fisheries and rainforests by logging companies, including his own in Makira.

He and his ministers were involved in many suspect deals in logging, fishing and gambling businesses. Critics, and there were many, held him responsible for the spread of corruption and political instability.

A political grandmaster, he engaged endlessly in political manoeuvring and knew how to compromise both supporters and opponents. The quality and financial discipline of the public service declined under his administrations.

He appointed and trusted unsuitable and unqualified people, some of them complete rogues. He undermined public service administration by ignoring and altering administrative rules or general orders.

As a Makira politician, he tried to promote development in Makira from the time he entered politics in 1970 but his ambitious ideas were never realised. In the 1990s, He was generous with his constituency funds and revenue from his own logging company and business.

Most of the projects were unproductive and unsustainable as canoes, engines and chainsaws broke or became unusable— but his contributions to the West Makira Games proved more long lasting.

Mamaloni’s legacy was also psychological. While critics maintain that he created a Mamaloni Way, a political style that has failed the country, he engendered a strong sense of self-belief in Solomon Islands after years of British condescension.

Mamaloni was a very sociable Solomon Islander, who preferred informality and liked nothing better than sitting round chewing betel nut, telling risqué jokes and storying, or playing darts.

A wartime child of Makira, like his father he became an Arosi araha and political leader, He was a four-time husband and father; a businessman and entrepreneur; and a member of a small western-educated elite who became a dominant big-man in a post-colonial political system. While all prime ministers have memorable characteristics,

Mamaloni was perhaps the most typical Solomon Islander of them all. He was arguably the most significant Solomon Islander of the 20th century, probably the most controversial, and certainly the most popular.

Understanding ‘Solo’: A Biography of Solomon Mamaloni by Christopher Chevalier was published online in 2022 at http://hdl.handle.net/1885/262993 and a revised printed edition to commemorate the 25th anniversary of his death will be on sale in the first half of 2025.

By Christopher Chevalier and Clive Moore