Solomon Islanders who changed global history

By Michael J Field

So why, someone might ask Caroline Kennedy, was the fact that your father was saved by a couple of Solomon Islanders obscured for so long?

And while at it, perhaps ask her just why her father, then Lt jg John F Kennedy, managed to lose PT-109, one of the fastest fighting ships for its time.

Caroline Kennedy, 64, is now the United States ambassador to Australia and is heading to the Solomon Islands to mark the 80th anniversary of the 1942 Battle of Guadalcanal in which over 30,000 Japanese and Allied men were killed.

It’s more than just a church service though; the anniversary marks Washington DC’s bid to renew its influence in the South Pacific and suppress growing Chinese influence. Kennedy will be carrying a message of Western values, family connections and loyalty. Of how the Solomons was “freed”, albeit returned to colonial rule.

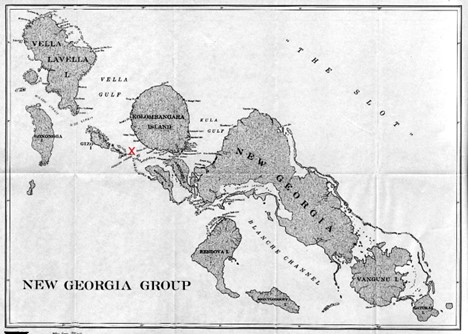

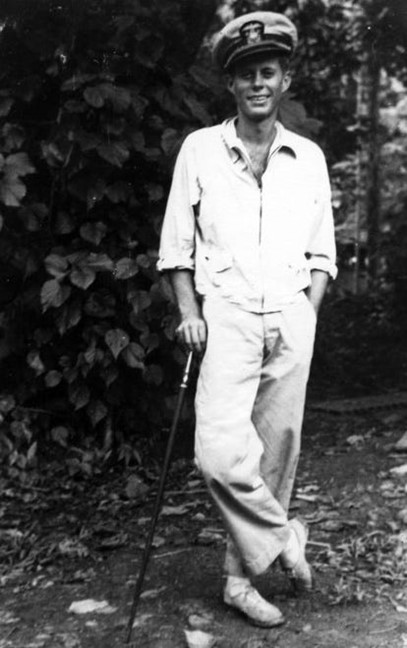

For the ambassador, the family connection is her assassinated father, JFK, who captained a fast patrol boat during the Solomon’s campaign, operating out of a base at Rendova. On the night of August 2, 1943, while in the Blackett Strait near Gizo, the 24-metre long PT-109 was idling in the darkness when it was rammed and sunk by Japanese destroyer Amagiri.

A mythology around the incident has grown, especially when Kennedy became president in 1961, and it was never clear why PT-109 had not been able to get out of the way to fight back. That was its job. At the very least, it raised questions over JFK’s watch keeping abilities.

After PT-109 was cut in half, Kennedy managed to save most of his crew, swimming to a Japanese held island.

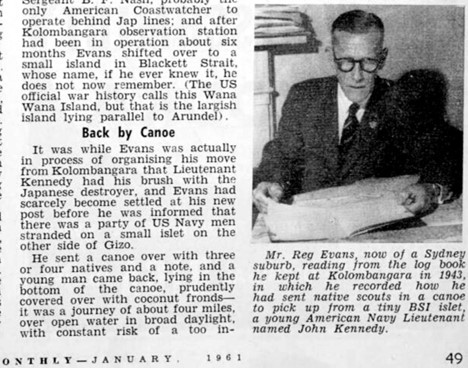

In due course two Solomon Islanders, Eroni Kumana and Biuku Gasa, found the men. They were patrolling for an Australian coastwatcher Reg Evans, based on Kolombangara, who had spotted the wreckage of PT-109.

After initial tense moments when the islanders pointed their submachine guns at the survivors, unsure if they were American or Japanese, Kennedy convinced them they were friendly.

Kumana gave an interview to a travel writer: “This man on the beach, he was lost and upset. He was shouting at me, but I couldn’t understand him….

“I put a bullet in my rifle and pointed it at the man’s head,” Kumana said. “And then I pulled the trigger… The gun jammed.”

Asked why he tried to kill JFK he replied: “I thought he was a Japan-man. All you white people look the same.”

As the mythology goes, Kennedy carved a message on a coconut husk and Kuman and Gasa took it to Evans. JFK was then taken by Kumana and Gasa in a canoe to Evans and all were later rescued by the United States.

For the most part, Kumana and Gasa then disappeared from the story, while Evans became the purported hero. When Kennedy defeated Richard M Nixon for the presidency, publications like Pacific Islands Monthly and Reader’s Digest sought out Evans who seemed more anxious to assert no New Zealanders were involved. The closest mentions of Solomon Islands were references to “natives”.

In the more insulting part of the story, Kennedy invited Kumana and Gasa to Washington to attend the inauguration in January 1962. Officials of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate under head John Gutch, halted Kumana and Gasa in Honiara and prevented them from going on. Two white officials of the protectorate went instead. No explanation was offered. Gasa’s family believe the British viewed the two men as simple village men and not well dressed.

Amagiri’s Lieutenant Commander Kohei Hanami attended the inauguration and acquired fame as the man who nearly killed the president.

Two years later, Kennedy was assassinated “I mourned for a whole week upon hearing of my friend’s death,” Kumana said.

Evans and other white men involved in the rescue were given medals. Kumana and Gasa were not.

Gasa died on November 23, 2005. Kumana died on August 2, 2014.

Caroline Kennedy, in part, owes her existence to them.